OK, here is a fun set of philosophical

puzzles, courtesy of current philosophers like Doggett, Egan and Kind

… English is pretty comfortable talking about perception-like

imaginings (imagine a sunset), or belief-like imaginings (imagine

that John Steward is going to run for president in 2016), but are

there desire-like imaginings? If so, what would they be like? What

role would they play? Is there a natural way to talk about them?

Doggett and Egan call them “i-desires” and admit that English

doesn't usually talk this way. Kind asks if there are any other

natural languages that do talk about desire-like imaginings.

I for my part, have had several

reactions here, and I'm sorta still processing them, but hopefully

this blog post will be a little less confused about it, than my chats

and emails so far, but not all the way to a scholarly article on it

or anything. One of the reasons that desire-like imaginings would be

handy if they existed, is that could serve explanatory roles parallel

to actual desires in a variety of cases where there seems to be no

parallel actual desire. So one of Kind's examples goes like this.

“A desire-like imagining is meant to be "a conative state that stands to desire as imagining stands to belief" (Doggett and Egan). The standard case of desire-like imagining is the conative attitude we take towards a fictional character -- as when I [want] Tony Soprano to get away from the cops. I don't believe that Tony Soprano is running from the cops; I (belief like) imagine it. And likewise, I don't want Tony Soprano to get away from the cops, I desire-like-imagine it.”

Or for

Egan

“So for example, believing that the Packers are about to blow their lead in the 4th quarter of the NFC championship game might make me nervous. But not just all by itself. It's got to team up with a desire - for example, the desire that the Packers go to the Super Bowl. (That's why when I believe the Packers are going to blow the lead, I get nervous, and when Ned Markosian believes the Packers are going to blow the lead, he gets excited.) Sometimes, when I imagine stuff, I get that same kind of affective response. For example, when I imagine that Tony Soprano is in danger of getting caught by the feds, I get nervous. How come? If we think it's the same model, we'll want some state that plays the same kind of role in teaming up with my imagining that Tony is in danger to produce my nervousness that my desire that the Packers win played in teaming up with my belief that they were going to blow the lead. Tyler and I don't think we can count on there being a for-real desire around to play the role in all the cases where we get the affective responses. (I don't have the for-real desire about mobsters evading capture. I don't have the for-real desire about the content of the fiction not including Tony's capture. No other candidates seem to do better.) So we think there needs to be a state that stands to imagination as desire stands to belief.”

So the first thing I want to argue is

that distinction we are looking for in these examples is the

difference between a for-real-desire and a fictive-desire, not the

difference between a for-real-desire and an imaginary-desire, and

this is traditionally talked about in terms of “diegetic layers.”

But maybe we'll be able to find other cases where the perception vs

imagination distinction is a better analogy.

In some genres, such as theatre,

almost all the fictional action is perceptual rather than imaginary.

In stage drama much may be intentionally left off-scene, and to the

imagination, and the special effects or lighting or such may be

unrealistic enough to require imaginary re-editing. But in, say, a

professional wrestling match, or a drag show, the fictional layer may

be entirely embodied, and the imagination may have almost no role to

play in making sense of the fictional context. It's possible to have

stories within stories, with multiple fictional diegetic layers, as

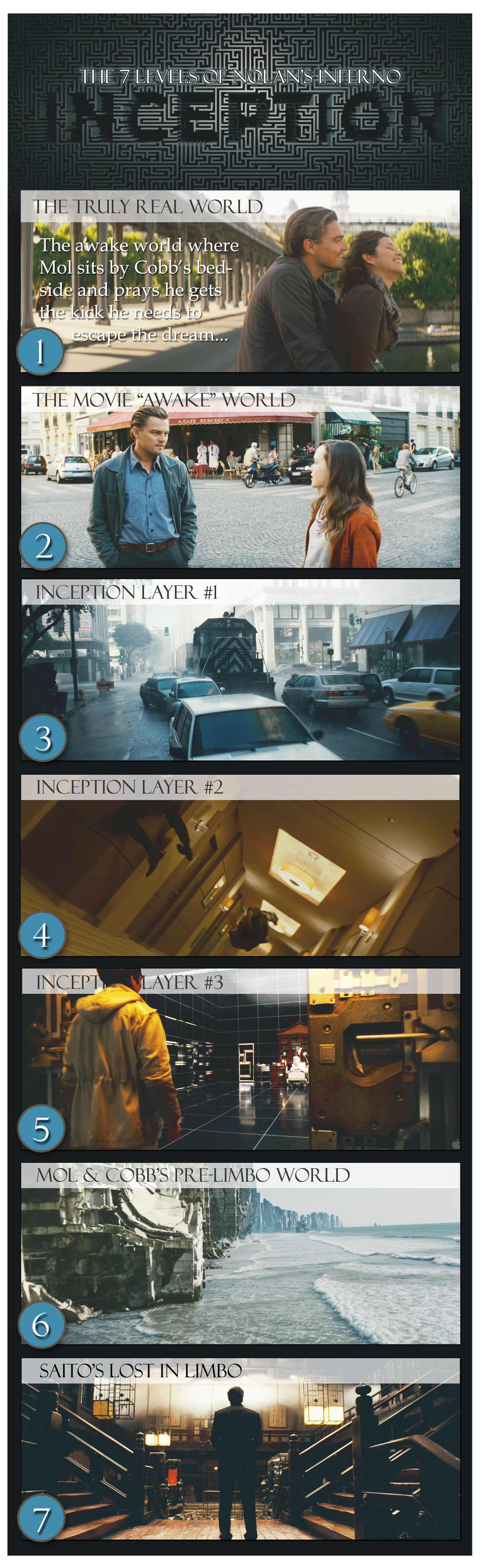

in Hamlet of 1001 Arabian nights. The movie Inception has six distinct fictional diegetic layers to keep straight at one point.

It's also possible to have multiple non-fictional diegetic layers, as

in video games or role-playing games. This can all get pretty

complex, and is a topic of much discussion among literature and art

theory types, and it's often important to actually doing the art and

crafts sides of movie or video game or theatrical storytelling well.

As the audience “identifies” more strongly with a particular

character, or becomes more fully “immersed” in the fictive

setting, the outer diegetic layers start falling away in our

phenomenological experience of the piece. But a clunky interface

moment, or an intentional reference to the world beyond the diegetic

frame can bring the attention back to the outer layers.

If we are being careful, imagining, pretending, and storytelling, are all slightly different activities, even though in practice they are often mixed together heavily. My account of desires about fictional stories is that I have

for-real desires, but desires which are organized by diegetic layer

by my training in the practice of being an audience member (or even

participant) in the storytelling genre. Contra Egan, I'm saying that

if I'm nervous that the cops are closing in on Tony Soprano (rather

than excited that the cops are closing in on Tony Soprano), that

means that I have a desire that the content of the fiction not

include Tony Soprano's capture, probably because at some level, I

have come to identify with him more than I have with the cops trying

to capture him. (Often because the storyteller has worked to make it

easy for me to identify with Tony, and harder to identify with the

cops pursuing Tony). I probably also have a desire that the

fictional contents be entertaining, internally consistent, and artistically satisfying and

that desire may wind up overriding my desire that Tony not be captured

in the fictional setting.

Organizing the desires involved in

consuming fiction by diegetic layer, has several advantages over

organizing them via analogy to the perception vs imagination

distinction. For one thing it can account better for cases where

juggling 3 or more diegetic layers are important. Similarly it can

account for the learning necessary for navigating diegetic layers in

unfamiliar narrative conventions, or for errors made when the

diegetic structure is complex (as it often is in video games and

roleplaying games). The distinction between perception and

imagination in contrast is usually more transparent, and while there

are perceptual illusions, and hallucinatory border cases, it's

usually pretty hard to confuse a perception like-imagining with an

actual perception, they are just so much less vibrant and full.

(Belief-like imaginings, delusions, and beliefs are much easier to

confuse phenomenologically.) Similarly, the organize-desires-by-diegetic-level strategy does a much better job with fictions that are

highly performative, where imagination is playing little role. On

Jan 15, Triple H, (a WWE “heel”)

broke kayfabe to console a crying fan. The problem is that the character Triple-H, portrayed by Paul

Michael Lavesque for the WWE, is supposed to be a bad guy. So

Lavesque's real world desire to comfort the crying child is in

conflict with Lavesque-as-acting-Triple-H's desire to fulfill the

antagonist role well, or Lavesque-as-Triple-H's desire to defeat his

opponent by any means necessary. The thing is as person, actor and

character, he is a fully embodied actual object rather than a merely

imaginary one. The character of Triple H is a fiction, a pretense,

and element of an an activity of pretending, and an element of a narrative construct, but he isn't strictly

speaking an imaginary being.

broke kayfabe to console a crying fan. The problem is that the character Triple-H, portrayed by Paul

Michael Lavesque for the WWE, is supposed to be a bad guy. So

Lavesque's real world desire to comfort the crying child is in

conflict with Lavesque-as-acting-Triple-H's desire to fulfill the

antagonist role well, or Lavesque-as-Triple-H's desire to defeat his

opponent by any means necessary. The thing is as person, actor and

character, he is a fully embodied actual object rather than a merely

imaginary one. The character of Triple H is a fiction, a pretense,

and element of an an activity of pretending, and an element of a narrative construct, but he isn't strictly

speaking an imaginary being.

My desire that Tony Soprano not get

caught is a intradiegetic desire rather than an extradiegetic desire,

or we could maybe say a fictive desire rather than a non-fictive

desire, but I don't think it's best understood as a desire-like

imagining. As Egan says, he's not convinced we'll have real world

desires for all cases where we get affective response, and my

intuition is similar, but I think fictional cases DO have real world

desires. However, maybe we can find something else that will look

like desire-like imaginings ...

Prof Doofenschmitz, the mad scientist villain of Phineas and Ferb, has at one point a musical number about how he wishes he hated Christmas, but how in fact he is pretty meh about Christmas.

Prof Doofenschmitz, the mad scientist villain of Phineas and Ferb, has at one point a musical number about how he wishes he hated Christmas, but how in fact he is pretty meh about Christmas.

The usual philosophical way of making sense of this situation is in terms of “second order desires” - desires that our desires be different than they are. Classically a junkie or pedaphile may intensely desire that they not desire the things they do in fact desire. The thing is, it seems that part of framing a desire to desire something, or not to desire something, would be framing some kind of conative state about the desired state. Often memory will do the trick. If I remember a time before I was a junkie, I might be able to desire that my desires be like they were back then. But phenomenologically, it certainly seems to me that sometimes the best we can do is “imagine” what it would be like for our desires to be a certain way. Maybe I no longer remember what it is like not to crave heroin all the time. Maybe I've never really hated Christmas, and have to imagine what it would be like to hate Christmas, as part of the process of desiring to hate Christmas. Maybe I'm so depressed that I can no longer desire to go to work, but I can still sorta force myself to go, and do so partly by framing an imaginary desire to go to work, and using that as an imperfect substitute for a genuine desire. Or to move it over to sexual desire, maybe I've read 50 Shades of Grey and find that hot. Maybe I desire that I desire to be beaten, but once I actually try it, it doesn't suit me and I realize that I don't actually desire it. I am in fact not much of a masochist, even though the thought of myself as being a masochist is appealing. My wife asserts, and I'm tempted to agree, that folks can even be in the tense state where the 2nd order desire is still present, even after experience has shown that you just don't have the first order desire.

One of the hallmarks of the

perception vs imagination distinction is the limited nature of

imagination, and it's phenomenological “paleness.” Imagination

is typically less detailed, less robust, and less intense than the

perceptual analogous. It has more “aboutness” in it too. A

perception can be a confusing welter of experiencing that we feel ourselves having

to work to organize into a coherent aboutness structure, but a

perception-like imagining has the aboutness structure more

apparent. This seems to be true of those 2nd order

desires that we have to frame via imagination (rather than memory, or

full actual presence). My i-desires in this sense are dimmer,

more tentative, less detailed. If I later feel the parallel

actual-desire it may not be that much like I'd imagined it.

Maybe there are other cases besides some 2nd order desires, where we have to imagine desires that we don't actually feel. In empathy, maybe I partially imagine what it is like to desire a heroin fix above all other things, when I am trying to understand the behavior of junkies, even though I don't have the second order desire to desire that I desired heroin above all other things. Indeed, these constructs in philosophy of mind are sometimes called pretend-desires, or off-line desires, and it's been suggested before, by Currie, that pretend-desires are the same thing as i-desires. Again pretending, imagining, and storytelling are closely related and intermixed, but not really the same activities. Also it's easy to make this kind of imagining sound like a belief-like imagining instead, perhaps I'm actually imagining a world where it was true that I desired heroin above all things. Phenomenological though, it seems to me that I can do both, and that they are distinct. I can belief-like imagine a world or situation where I have this desire as one of the facts of that world/situation. I could then write a fiction, or daydream about it. But trying to desire-like imagine that I crave heroin above all things feels possible a but like different project. Similarly, I see why people would think that in the case of fiction we are imagining desires that we don't really feel. It's just that I think part of how “involvement” or “immersion” in fiction works, is that we start to genuinely feel desires about the fictional context rather than just imagining how the fictional characters feel about their own fictional context. That's it! When I “empathize” with Tony Soprano, I may imagine what it is like for him to desire not to get caught (especially if the pacing is slow and introspective enough), and that may be a desire-like imagining, but because I am involved with the story myself, (especially if the pacing is more griping), I also have an intradiegetic desire on my own part that Tony Soprano not get caught within his fictional setting, and that's what accounts for my nervousness.

So in conclusion, like Egan and

Doggett, I'm optimistic that there are such things as

desire-like imaginings, and that they have some philosophically

explanatory roles to play in some cases (although how distinct they are from more familiar kinds of mental states I'm less convinced of). Like them I suspect there

isn't a good existing term in English for them, so i-desires seems as

good as any. I'm not aware of any foreign languages with clear terms

for i-desires. However, I think i-desires, are importantly different

from fictive desires. Fictions aren't always imaginary, and are

often partly imaginary and partly perceptual. The philosophical

explanations we want for most fictional contexts can be done more

elegantly with “real-world” desires aimed at fictional contexts

and organized along diegetic layer lines. (We really need a term for

desires that aren't i-desires, maybe a-desires?). But other cases, like

empathy, or 2nd order desires where memory or presence is

insufficient, might be much closer phenomenologically to "desire-like

imaginings."

For more info see

Amy Kind - especially The Puzzle of Imaginative Desire," Australasian Journal of Philosophy 89: 421-439 (2011) -

Andy Egan - especially “How We Feel about Terrible, Non-Existent Mafiosi” (with Tyler Doggett) Philosophy and Phenomenological Research

Alan Fine's old sociology book Shared

Fantasy: Role Playing Games As Social Worlds, University of Chicago

Press (Chicago, IL), 1983.

(and since I haven't been in academia a while I need to read most of these too ...)